Will there ever be another Steve Jobs?

Michael Bywater thinks not... and not just because of his charm, his tantrums, and his insistence on rounded rectangles

It's an enduring question: "Is (X) the new Steve Jobs?" The answer's always "no", of course. But last month, Inc. Magazine found a loophole and rephrased it as a statement, "Why the Next Steve Jobs Will Be a Woman", and tipped its hat to one Elizabeth Holmes.

She's the founder of Theranos, with a paper fortune of $4.5bn from raising money to do… to do something. Something with blood tests and weeny little bottles, Walgreens and a secret gizmo called Edison. She's got – or had – the support of George Shultz, Barack Obama and Henry Kissinger, who is still, I believe, alive.

Despite some of her big shots reportedly scuttling down the mooring warps in the wake of sniping (the Journal of the American Medical Association, for example, said earlier this year that, "Theranos has operated in stealth mode for more than a decade, not publishing anything in the literature while preparing to change the entire [American] health system"), Holmes remains gung-ho, insisting it's fantastic, world-changing and insanely great. Familiar? "Comparisons to Jobs," reported The Sunday Times a couple of weeks ago, "stem partly from her insistence on only ever wearing black turtleneck sweaters, so as to free her mind".

Gadget and tech news: In pictures

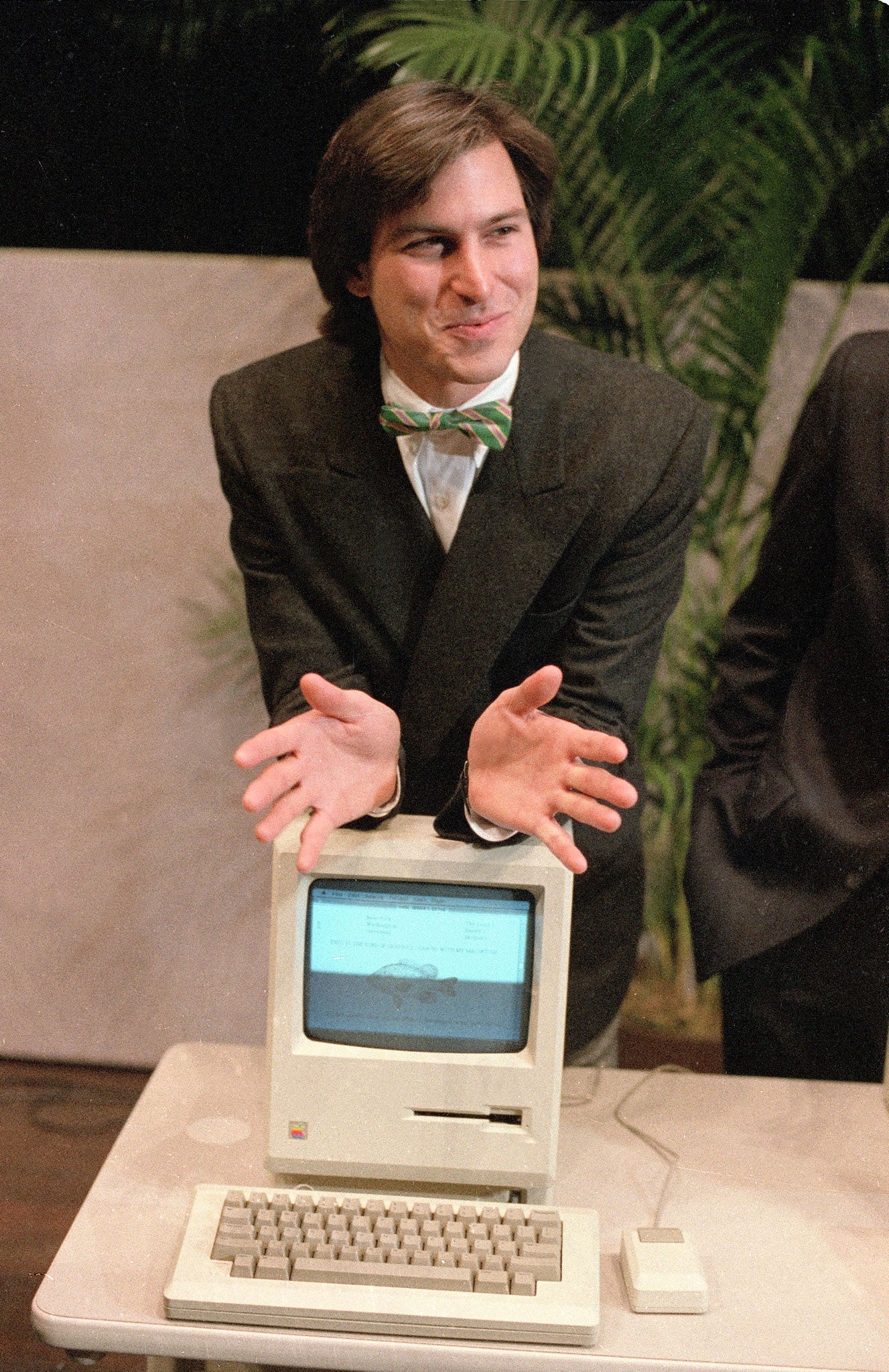

Show all 25Well, damn me. Turtlenecks. It's a done deal, even though Jobs, when I first met him in California, was wearing a ratty old Pendleton shirt and blue jeans. Sometimes he worked an unforgivable suit, sometimes a bow tie and one of those wife-swapping dude moustaches. He didn't actually get handsome until the mid- to late 1980s, and the turtlenecks didn't start until the late 1990s, when Issey Miyake sent him 100 of them and that was that.

But that's nitpicking. The rest of Elizabeth is very Steve. The secrecy. The ineradicable self-confidence. The game-changing innovation which nobody understands and which half the time seems like bullshit, and the other half like it might be the beginning of something huge.

Late last month, Steve Jobs, the Aaron Sorkin and Danny Boyle biopic, opened on limited release in the US. Variety splashed it as "Steve Jobs Bombs" after it grossed a "measly $7.3m" on its opening weekend. We might quibble with that "measly"; at the current average of $8.50 for a movie ticket, that means 860,000 people went to see a film about a guy who made computers – that's a lot of people.

But in reality, they didn't go to see a film about a guy who made computers. Nor was that the film they got. Which is fine, because if we're going to wonder who the next Steve Jobs might be, we should remember that the last one was not a guy who made computers. Jobs was a guy who got other people to make them to suit his own vision: bona-fide geniuses – Google them; you'll see – such as Bud Tribble, Alan Kay, Burrell Smith, Jef Raskin, Randy Wigginton, Bill Atkinson, Andy Hertzfeld and Apple's co-founder , phone phreak and hardware god Steve Wozniak. Virtuosos all, in search (whether they knew it or not) of a conductor. And, of course, people such as the designer Susan Kare, whose (literal) iconography defined the Macintosh look from the very outset.

No; Jobs was a guy who made his customers believe that the computers he got other people to make were better than the computers anyone else made, or ever could make. He was, in short, the perfect example of that American archetype, the fellow selling snake oil out of the back of a wagon who really believed that his snake oil did all the stuff he claimed it did.

And, crucially, it worked. It worked because, like the movie, the Macintosh – thanks not least to Kare – bombed.

Let me explain. Until 1984, if something went belly-up in the computer, it snarled at you: "CMOS checksum invalid.

"The CMOS will be reset to the default configuration and will be rebooted.

"CMOS Reset (502)"

After 1984 – the Year of the Macintosh – you'd get, instead, a cute little picture of an old-style anarchist's bomb with a burning fuse. The computer was still temporarily buggered. It didn't even tell us how it was buggered. But we felt it loved us and wanted to help us. That was the genius; that was what Jobs did. If the two big questions are how he did it, and who the next one will be, the movie skirts them almost entirely.

Sorkin is the screenwriter behind The West Wing, A Few Good Men and The Social Network. Damn, but he knows what he's doing. And for Steve Jobs, he chose to frame the story as a triptych, based around three product launches: the Mac 128K; the NeXT computer, which Jobs fathered during his exile from Apple in the Interregnum of the Nobodies, kicked out by an ex-Pepsi guy who was startlingly out of place and his depth; and, finally, the iMac, which restored Apple's corporate fortunes.

You can see the reasoning. Here's a three-act drama with a timelock on each act: Steve's on stage any moment now, so let's talk. Guys who are on stage any moment now don't talk about life stuff, relationship stuff, emotional problems or resolving their inner demons. They pace. They rehearse bits of their presentation. They wonder if the projector will work. They fret. But not so in the movie. On-stage-any-moment Steve talks.

It feels more like a play than a film, and Steve talks because that's what is true: not historical true or even true truth, but it's story true. And the story is the old, old one of the hero's emotional voyage, told through that very American trajectory of personal growth and the idea that a man's business fortunes somehow mirror his stature as a sensitive, aware human being. Steve Jobs is the story of a man, a prickly, wrongly made man, who denies his daughter's paternity and estranges himself from her and her mother, and only in the end, after success, disgrace, expulsion and his return to his own Ithaca – Apple Inc of Cupertino – does he find redemption through reconciliation. I say "Ithaca" because Steve Jobs is one of the oldest of stories: the story of another Odysseus trying to get back home.

But there's another story waiting to be told. And it's the story of that headline. Is (X) the new Steve Jobs? Well. OK. No. So, not much of a movie there, either. But really: there won't be a Next Steve Jobs. Nothing to do with snake oil. Nothing to do with the aesthetic sense which had him obsess about merging graphic and industrial design, or fretting about the precise curvature of a rounded rectangle. Nothing to do with his anti-shampoo period, or his charm or tantrums or bullying or sweet-natured cajoling or the Indian Kainchi Dham ashram which remade (he said) his attitude to life, and to which he was subsequently followed by Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg.

Nothing to do, either, with the fellow I knew slightly, with whom I spent a cheery half-hour rearranging the chairs in The Red Fort Indian restaurant in Dean Street for reasons I still don't understand, nor the hour I spent in LA trying to get him to let me call my mother on his mobile phone (so cutting edge it had a sort of car battery in a shoulder harness) until he finally admitted it only worked in Northern California, but he'd brought it to LA as he didn't want people to think he was behind the curve. "But," I said, "what if people think you're a madman?" "Yeah," he said, "fine. Their privilege. But you know? They'll think, 'That guy's a madman but look at his phone! He must be doing something right...'"

And so he was. And the most interesting bit was that the something consisted of changing the game – his own game, personal computers, first, then a raft of other tech devices – while he was actually playing it.

Tech superstars now change others' game. "Disruptive technology", they call it. It's what Elizabeth Holmes is doing (or may be doing) with her blood-testing stuff. It's what Uber's Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick are doing with cabbies. It's what Jan Koum did with WhatsApp and Ted Livingston with Kik: disrupting people's emotional safety and security, because if your partner has Kik or WhatsApp on his or her phone, you are so screwed. (Or, rather, he or she is, and not by you.) Jeffrey Skoll's eBay disrupts people's attics; Amazon's Jeff Bezos disrupts every retailer on the planet; Facebook has disrupted expectations of privacy; Larry Page and Sergey Brin, with Google, have disrupted not only the web, but the entire neutrality of enlightenment by serving us only stuff that we want to hear… on it goes.

Some of this is laid at Apple's door, and thus at Jobs'. But the difference is that Jobs built the platforms, Mac, Pod, Pad, Phone… Or, rather, he made the platforms attractive, appealing, aspirational. Technology acquired the status of clothing. It advertised something about the user (or maybe "wearer"): coffee shop, Shoreditch, hipster, Moleskine, flat white. To see that a computing device can itself make specific declarations of the sort of person the user wishes to appear, that was Jobs' specific genius. Jobs, if you like, invented coffee. The others – the Facebooks and Ubers and Tinders and Grindrs and all the rest – have invented Starbucks et al.

It's not just that, of course. First, the money's too big. The days of the garage (hi there, Hewlett-Packard!) are over. The due diligence is too diligent. Regulation is too regulatory. The market is too saturated. Above all, with the supremacy of Web, Cloud and Always-Connected, the device on which we get access will become as irrelevant as the shoes we wear to catch the bus. They may say something about you, but they're not what's getting you to your destination.

In Outliers (2008), Malcolm Gladwell postulates that many of the Generation One big names in technology – Bill Gates, Jobs, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, Google chairman Eric Schmidt, Sun Microsystems' Scott McNealy – became big names not just because of talent and hard work, but because they were born at just the right time, in the mid-1950s. Any earlier, says Gladwell, and they'd have been absorbed into the sclerotic, corporatist ranks of IBM; any later and they'd have been snapped up by Microsoft and its co-giants. The time of the tiny tech start-up has passed. For all the success of Meow Meow Star Acres, say, its founder, Naruatsu Baba, will not, ever, be the next Jobs. What's missing is the drama of watching a landscape change.

So Elizabeth Holmes could just be the next Jobs. Or someone like her. Not in IT or personal tech, but somewhere we haven't even noticed, in something we haven't even thought of. And whoever it is will need a Jony Ive. Apple was a great concerto. If Jobs was the conductor and the Apple staff were the orchestra, then Ive was the virtuoso pianist who made the whole thing glitter.

Tech won't change the world now, because it already has. There won't be another Steve to give the guy in the favela and the guy in the Park Avenue penthouse something in common – their smartphones, all of which aspire to the condition of the iPhone. The time when the tech revolution met elegant consumer aesthetics will not come again. Something will come; but we have no idea what it will be. All we know is that something will happen because someone, somewhere, will do something spectacular. What? Who? Where? When? How? The old journalistic questions. And the old journalistic answer: not a clue.

'Steve Jobs' (15) is on general release now

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies